Pauline Kaldas’ office is sunny and bright, full of books, a couple camel figurines, and a round table in the center. We take our seats around the table, like a family sitting down for dinner, as a window faces us and projects golden-hour light onto her face like a spotlight. Considering who we’re talking to, this is appropriate.

Dr. Kaldas is a tour-de-force writer who has written in nearly every genre from poetry to creative nonfiction–she’s even penned a multicultural literature textbook. Born in Egypt, she immigrated to the United States at eight and a half, living in Boston with her family and attending first Clark University to earn dual bachelor’s degrees in English and business, then the University of Michigan and SUNY Binghamton for her master’s and Ph.D. in English, respectively.

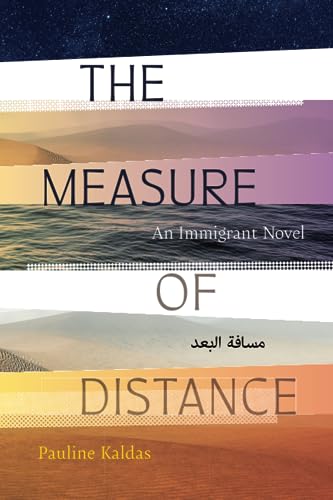

Her latest–The Measure of Distance: An Immigrant Novel–was out this September. And Kaldas generally writes about her Egyptian identity and Arab-American immigration, “My writing comes directly out of that immigrant experience,” she says, “which is why my writing is constantly evolving around that issue. So working on it in these different forms, gives me a new way of looking at it.”

Beyond being a writer, Kaldas is the mother of two daughters, wife to fellow Hollins professor TJ Anderson III, and a lover of a good novel and a rom-com.

“All I can say is that life will be filled with the reasons for why you can’t get to your writing,” she said. “And there are no excuses. If it’s something you want to do, you just have to do it.”

You said you read fairytales as a kid. How did this influence your writing today?

I came to the United States when I was eight and a half. I had gone to a school that taught British English—that did not mean that I could speak English in the United States, and especially not in Boston. When I got here, I couldn’t understand a word anybody said. After about six months of silence, things began to make sense. I started reading fairy tales and I really just loved them. They took me out of my world, out of all the difficult things that I was facing. When you fall in love with reading, at some point, there’s a natural tendency to then want to create your own stories.

I don’t write fairy tales, but I think what fairy tales taught me is the act of imagination. What I write about is very much real, but within that reality, that is still an act of imagination. And obviously, in fiction, you have to be able to imagine what you don’t know. I think fairy tales taught me that you can go beyond reality. And one of the things that happens in my fiction is that I often have some element of reality—I begin with somebody I knew, and the incident that happened. But in my family, I never get the whole story [about an uncle or a cousin], which is really frustrating—I get bits and pieces of things. And when you are stuck in this space where you’re not getting the whole story, fairy tales taught me about a leap of imagination. If I’m not being told the story, then I’m going to imagine this story. I think that’s something that I learned from fairy tales—you don’t have to be grounded in reality. I begin with reality, but then I just go somewhere else, wherever my imagination will take me.

In college, you wanted to major in English and be a writer—what did your parents say?

They were not pleased—they were immigrants—and I think it’s really important to put the reaction in the context of what it means to be an immigrant: they came here because they wanted a better life. And for many immigrants, the definition of a better life is centered on economics—you know, get a good job, make money, buy a nice house, have a nice car. That’s what it means for immigrants to be able to succeed in America. Those are the things that make immigration worth it, because of all the things that you give up.

I’m a one and a half generation immigrant because I came as a child—I’m not first because I didn’t come as an adult. And I’m not second, because I wasn’t born in the United States. But the pressure that immigrant parents put on the children who are generally second generation is a very heavy burden, and it is a burden that really is on economic success—become a doctor, become a lawyer, make money, acquire the material goods that signify success.

That is often what is perceived as the American dream, right? I think that second generation—or the one and a half generation—often stumbles on a different American dream, which has to do with following your passion, and doing what you love. And that is something embedded in American culture.

In Egypt, they’ll tell you what you want to be when you grow up. In America, they will actually ask you what you want to be when you grow up. This idea of following your passion, of doing something that you love, or dedicating yourself to something that is really meaningful to you, I think is the American dream that many of us who are children of adult immigrants stumble upon, and we take hold of that dream. And it is a dream that does not match with the American dream that our parents have. I think we’re actually both following an American dream, but they’re two very different American dreams—that’s what happened to me: I think I caught this idea of doing what you love. I loved reading, I loved literature, I loved writing. And that’s what I wanted to do. So for me, that was the American dream that I got a hold of and kept going with.

Let’s talk about The Measure of Distance. You write in all genres, so how did you know this one was going to be a novel?

I love to read novels more than anything else—I always knew I really wanted to write a novel. But, I wanted to be with my children. That mattered a great deal to me. I started The Measure of Distance when my younger daughter went away to college. And I said this is it, there’s no more excuses—if I’m going to write a novel, I now have that space both in my mind and in my life to be able to do that. The idea for the novel came in 2010 from our [family] trip to Egypt. That’s when the ideas started to ferment. It was around 2015 or 2016 when I sat down to write it. So, I set out to write a novel very purposefully. That doesn’t mean it went smoothly—but it was intended to be a novel from the beginning.

I also like the challenge of new forms. I write mostly about being Egyptian, as well as Arab American immigration—so how do you continue to make the same subject interesting? And I think for me, it’s like, what does it look like in poetry? What does it look like in memoir? What does it look like in essays? What does it look like in a novel? And what does it even look like in a textbook? And then I wanted to know what it would look like in a young adult book.

Immigrating was a pivotal moment in my life. It transformed my identity. If I had stayed in Egypt, what would have happened to me? Who would I have become, where would I have gone to school? Who would I have married? What children would I have had, what career? Would I have become a writer if I had stayed in Egypt? I think I wouldn’t have.

Do you have any new projects in the works you can share with us?

I’ve got a book for middle schoolers that I’m trying to find a publisher for that’s, again, based on those early years that I spent here in the United States. TJ and I did a picture book together that we’re trying to find a publisher for—it’s about a cat that we encountered when we were in Morocco. And I’m not sure if this next project is a novel or novella, it might be a novella–it doesn’t seem to want to stretch to become a novel–but I’m keeping that open as an option. I’m working on some short stories that I’m hoping will become linked to [other] short stories and will evolve into a complete narrative that has to do with objects that we bring with us when we travel. And, also, an anthology of Arab American scholarly essays that I’m co-editing with two other people. Yeah, that’s a lot of stuff!

Written by Ruby Rosenthal (MFA ’24) and Hen Graham (MFA ’25) with interview support from Marta Regn (MFA ’24) and Kat Humphreys (MFA ’25). This interview has been condensed and edited for grammar and clarity.